Supermarket Pull Systems: The Foundation of Lean Replenishment

Supermarket Pull Systems: The Foundation of Lean Replenishment

Part 1: Why the supermarket model works, and what makes it hold in real operating conditions.

Introduction

Think back to when grocery shopping felt effortless. You walked in, aisles were tidy, everything had its place, and when something came off the shelf, it didn’t stay gone. There was a steady, almost invisible rhythm behind the scenes making sure it returned before anyone noticed.

That experience does not depend on perfect forecasts or flawless supply chains. It works because the system is designed around actual consumption. Customers take what they need. The store replaces exactly what was taken. Clear limits prevent excess. Simple visual signals keep the rhythm steady.

That logic still holds up today. As product variety increases and operating conditions change faster, systems built on clear locations, fixed quantities, and replenishment triggered by use continue to perform. They absorb variation without overreacting. They make problems visible without stopping the flow.

Supermarket pull systems bring that same stability into production environments. They create order without complexity, responsiveness without chaos, and availability without excess inventory.

- Why it works: replenishment follows use, not prediction.

- Where it fits: between processes that shouldn’t be hard-linked in flow.

- When to use it: repeatable part families, standard containers, reliable replenishment lead time.

- What to remember: supermarkets are governed systems, not storage areas.

Origins: What Toyota Saw That Others Missed

When Toyota engineers visited the United States in the 1950s, they toured American factories like everyone else. They saw long production lines, high output rates, and large batches planned weeks or months in advance. Those systems impressed executives at the Big Three.

But what truly caught Toyota’s attention was not inside the plants. It was in American supermarkets.

Stores such as Piggly Wiggly, one of the earliest self-service grocery chains, let customers pull products directly from shelves, clearly labeled by item and price. Shelves had fixed locations. Quantities were limited. When something ran low, it was obvious. Replenishment followed what customers actually took, not what managers predicted they might want next week.

Taiichi Ohno and his colleagues saw something Detroit largely overlooked: a system that stayed responsive without relying on forecasts or excess inventory. Ohno later reflected on this insight in Toyota Production System.[1]

- Speed and scale

- Large forecast-driven batches

- Inventory as a buffer

- Fixed locations and clear limits

- Replenishment triggered by use

- Visibility when something breaks

In plain terms: Detroit was captivated by output. Toyota was captivated by the rules that kept shelves full without overproducing.

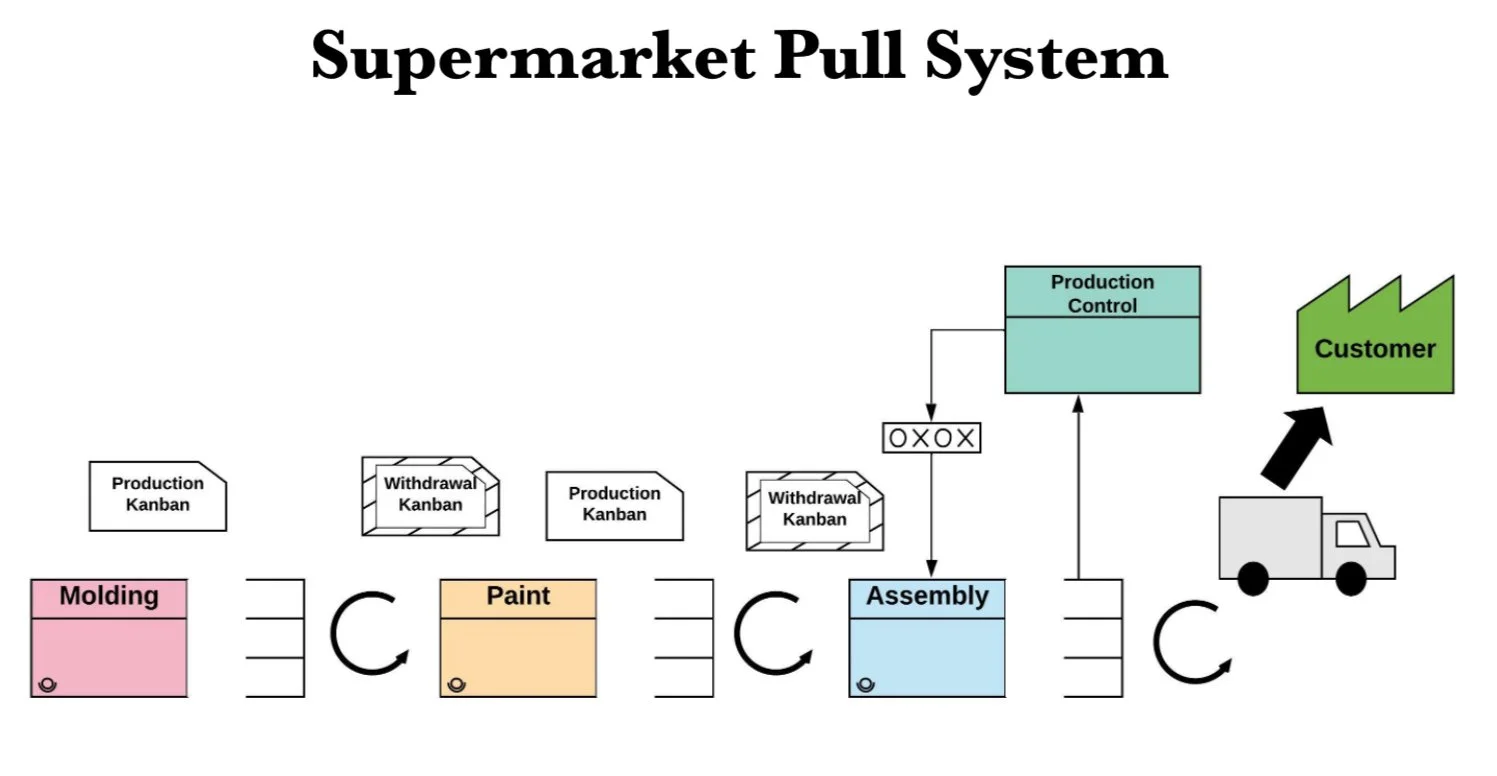

What Is a Supermarket Pull System?

Imagine a mid-sized manufacturer that produces industrial pump assemblies. One machining cell produces stainless steel shafts used across multiple pump models. Final assembly consumes those shafts at a steady but variable rate.

Instead of scheduling shafts daily or pushing large batches downstream, the team uses a supermarket pull system.

-

1

Items live in designated locations

Finished shafts are stored in a labeled rack called Shaft Supermarket A. Each lane corresponds to a specific shaft type. Assembly always pulls from the same location.

-

2

Every item has a maximum quantity

Each lane holds four standard containers. No more, no less. The limit exists to cap inventory and expose problems, not to maximize storage.

-

3

Visual signals show when to reorder

Each container carries a kanban card. When assembly pulls the last container from a lane, the card moves to the kanban post. The trigger is immediate and visible.

-

4

Consumption drives production

Assembly uses one container of shafts. That kanban card authorizes machining to produce exactly one container to replace it. Nothing is produced unless a card arrives. Pull one, make one.

The rule is simple and enforced: you only produce what gets consumed.

As Art Smalley explains in Creating Level Pull and Christoph Roser reinforces in All About Pull Production, supermarkets stabilize production by deliberately capping inventory and tying replenishment directly to actual use.[2][3]

In plain terms: you are not “planning” inventory into existence. You are replacing what was actually used—one container at a time.

The Just-in-Time Connection

Right Part: items are stored in designated locations with clear addresses.

Right Amount: maximum quantities prevent overproduction and standard containers define replenishment quantities.

Right Time: visual signals trigger replenishment when, and only when, consumption occurs.

Traditional manufacturing pushes work based on schedules and forecasts, often building inventory weeks ahead of need. Just-in-Time inverts this logic. Pull from actual consumption, produce to replenish, and let real demand set the pace.

The supermarket is the physical manifestation of that inversion. It provides a controlled buffer that smooths variation while preventing the waste of overproduction.

In plain terms: the supermarket gives you availability without giving you permission to overbuild.

Where Supermarkets Fit in the Production Flow

- Between processes with different cycle times, such as stamping and assembly

- Between shared resources and multiple customers, where one process supplies several downstream users

- At process interruptions or constraints, such as batch heat treatment

- Before the pacemaker process, enabling final assembly to build any mix, in any sequence

What supermarkets are not: random storage locations, overflow areas for excess inventory, or places to hide problems.

In plain terms: supermarkets belong where you need decoupling—without losing control.

Why Supermarket Pull Still Matters Today

Supply chain volatility has become the norm. Manufacturers continue to struggle to find and retain skilled workers, and new employees must become productive quickly, as outlined in Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute’s 2024 manufacturing talent shortage report.[4]

Product variety continues to increase. The average grocery store carried roughly 7,000 SKUs in 1970; today’s stores carry more than 40,000. As discussed in Specright’s overview of SKU rationalization, each additional SKU demands its own location, signal, and limit.[5]

Inventory discipline is no longer optional. Inventory carrying costs typically run 20–30 percent annually, according to the Institute for Supply Management, tying up capital that could otherwise be invested in people, equipment, and improvement.[6]

On the shop floor, people need to know three things instantly: what do I make next, how much, and when. Supermarket pull answers all three at a glance.

In plain terms: the more complex the world gets, the more valuable simple, visible rules become.

When to Use Supermarket Pull Systems

Supermarket pull works best in make-to-stock environments where products are built ahead of demand and stored until needed.

- Production is repetitive: the same parts or families are produced regularly, allowing replenishment to settle into a stable rhythm.

- Consumption follows a predictable range: demand varies, but usage remains within a recognizable band.

- Containers are standardized: fixed container sizes define replenishment quantities and eliminate informal batch decisions.

- Replenishment lead time is reliable: the supplying process can consistently replace what is consumed within a known timeframe.

- Space supports FIFO and visibility: clearly defined locations make flow and abnormalities obvious.

When these conditions are in place, the supermarket can be governed with a small set of explicit elements. Those elements define how pull is authorized, how flow is protected, and how discipline is maintained.

Key Components (Defined)

A controlled physical buffer with fixed locations and maximum quantities that decouples processes while maintaining inventory discipline.

The production authorization triggered by downstream consumption, signaling exactly what must be replenished.

A rule that ensures the oldest inventory is used first, protecting lead time and exposing hidden delays.

Explicit caps on work in process that prevent overproduction and make constraints visible.

The visible FIFO queue where kanban signals from consumed material are collected and sequenced, defining what gets produced next.

Clear, enforced rules that define who can take material, in what quantity, and under what conditions.

The known, measured time required to replace what was consumed, used to size and protect the supermarket.

Together, these elements form a governed pull system. When any one is missing, the supermarket quickly degrades into unmanaged inventory.

What’s Next?

Understanding the logic is one thing. Seeing it applied in real operating environments is another.

In Part 2, we will walk through real supermarket pull implementations, including where teams get it right, where they struggle, and how sizing and discipline determine success.

References

- Ohno, T. (1988). Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Productivity Press.

- Smalley, A. (2004). Creating Level Pull. Lean Enterprise Institute.

- Roser, C. (2022). All About Pull Production. CRC Press.

- Deloitte & The Manufacturing Institute. (2024). Manufacturing talent shortage coverage: Manufacturing Dive link.

- Specright. (2025). SKU rationalization overview: Specright link.

- Institute for Supply Management. (2022). Inventory carrying cost: ISM link.